追悼・室伏鴻 “Ko Murobushi Faces Murobushi Kō: A stranger in his home country and in his body” / Katja Centonze(カティア・チェントンツェ)

In June 2015 the Japanese dance scene has been violently shocked by the sudden death of one of its most representative dancers. Murobushi Kō spread all over the world a new sensation of dance, an own challenge to the corporeal arts shivering his raw material on international stages and provoking cracks in countless artists and spectators.

Murobushi occupies a preeminent position in disseminating butō/Butoh overseas. Since Le Dernier Èden—Porte de l’au-delà (Paris, 1978), choreographed for SEBI and ARIADONE, he stimulated and inspired new dance solutions and waves in the international contemporary dance scene (Centonze 2006; 2010; 2014; 2015).

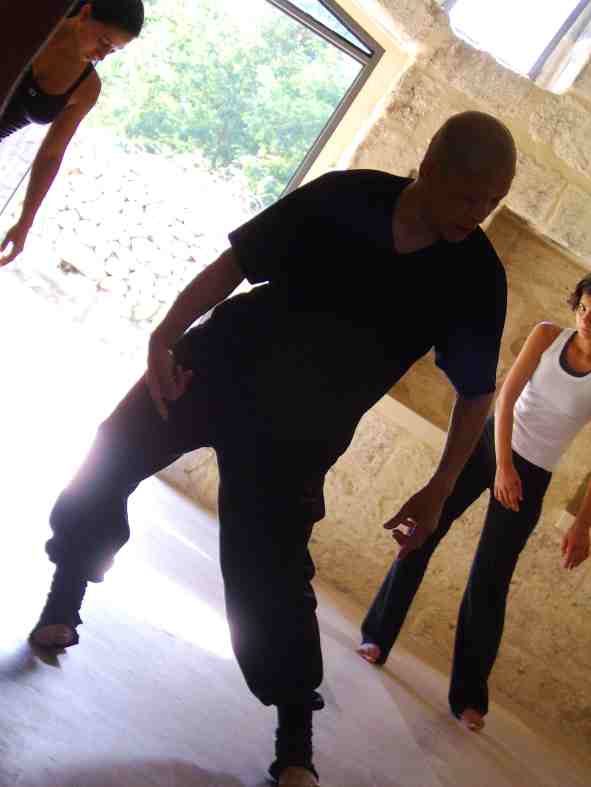

He also plays a fundamental role in re-addressing butō experimentation bridging contemporary dance and the avant-garde expression from the ’60s, while shaping bodies of young dancers up to our days (Centonze 2010; 2014).

Without any doubt, Murobushi is one of the most significant heirs of Hijikata Tatsumi’s dance-revolution. While incubating the seed of his master’s radical project of anti-dance, he forged his own path and original response.

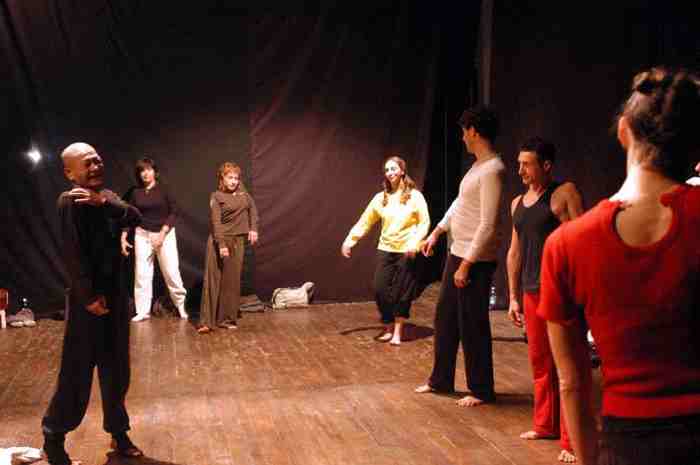

I met him for the first time in Ravenna thanks to the festival Ottobre Giapponese (first edition, 2003) directed by Marco del Bene, who asked me to curate the butō section. I played all my cards and tried to invite one of my favourite dancers, who, to my astonishment, accepted and came with his light designer Krisha Piplitz. The Byzantine city and its theatre, Teatro Rasi, hosted his impressive solo [edge 01], after an intense workshop and a conference of mine. Since then, wondering how an acclaimed artist could be so direct and open with somebody meeting for the first time, our indissoluble friendship has led us to endless discussions sharing even violent altercations.

Only some days after the Ravenna event, I went for a one-year research to Tokyo, which gave me the opportunity to witness closely his productions. His male company Kō&Edge was at its beginnings and he always involved me in discussions preceding and following his works: Bibō no aozora (2003) and Heels (2004), his choreography Giselle(s) for the female company Dansu 01 (2004) and his solo Subete wa yūrei (2004) (for a detailed study on these performances see Centonze 2008b; 2009).

In 2005 he invited me to see his re-enactment of Zarathustra performed by ARIADONE at Teatro Mancinelli in Orvieto. The performance was sold out and the theatre was crowded with spectators coming from different places.

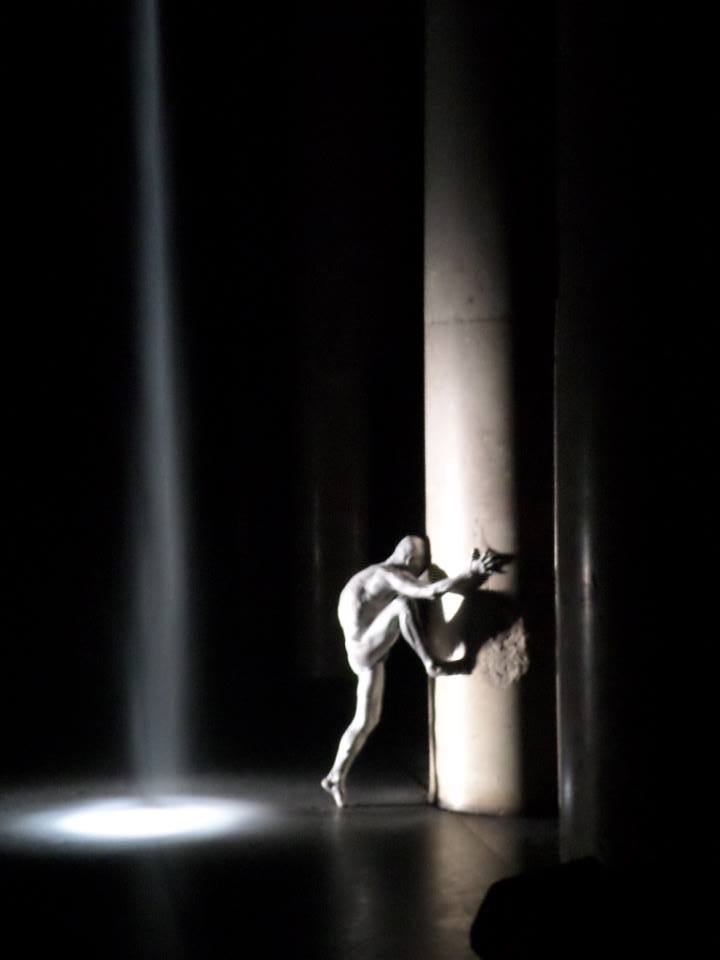

The next year we spent several days together in Venice. For more than a month La Serenissima was covered with Murobushi’s silver-body portrayed by Itō Miro, image chosen for representing the UnderSkin edition of Biennale Danza. His solo quick silver was performed twice, and from one day to the next the experiment changed drastically in tension and colouration of the aesthetic display, as if Murobushi would explore the other side of himself and his performative act.

One month later we met again, because he was also involved in the 50th Biennale Musica Venezia (2006) performing in Julio Estrada’s Murmullos del Pàramo.

In 2007 Andrea Pati, Annamaria de Filippi and me invited Murobushi to the festival Torcito Parco Danza I held in the countryside of Lecce. Our site-specific project, specifically entitled ATNARAT, aimed at overturning the post-modern myth of Tarantism and at re-considering the important role that the bodily aspect historically played. This experiment was based on my comparative study on Tarantism and butō as cultural resistance (Centonze 2008a).

Moreover, our intent was to revive the image, found in both phenomena, of the dead body in the harsh Salento nature among its ancient stones and layered history of oppression and self-defence. In this intercultural interaction local artists with a nomadic character and with the perspective of remapping their history were refracted by the identity of Murobushi. On the other side, Murobushi, who often insists on his nomadic character drawing on Deleuzian theories, mirrored himself in the hosting context.

During this festival the Japanese dancer presented two performances. On the first night he re-enacted an exceptional version of quick silver. Murobushi’s dance exploded into a ferocious and panic-spreading happening. Half-naked and covered by metallic acrylic paint, he improvised a violent and wild performance exploiting the entire space, which he organically revived. His body literally phagocytosed the environment and aggressively attacked the dominating silence of the venue. On that evening Murobushi manifested a contrastive relationship with the surroundings without any compromise.

There could not have been a better combination for our project between Tarantism and butō. Murobushi’s performances were simply superb. His quick silver, half between poison and medicine, reverberated the venomous spider detonating a fight between the Japanese avant-garde and the Salentinian phenomenon (for a detailed analysis of his performances see Centonze 2011).

His intoxicated and poisonous silver-body reflected his flowing and contaminated identities as if affected by contagion, an issue on which Murobushi worked for a long time.

About quick silver Murobushi writes:

It is both a venom and a medicine, which are made useless today, it is the Quicksilver [suigin], Mercury [mākyurī], Mercurius, but this is also our lost body [shintai]. (This answer, as this is the response, is therefore a messenger.)

In my body-technique [shintai gihō], there is something like stiffening muscles, bones, skin, dismantling them into pieces, or making them relax all at once in the moment I stiffened my entire body to the utmost limit, letting the cutaneous sensation divided into inside and outside reverse on itself and flow back as a Möbius strip band, but you do not know it, until you do not take a lethal dose of the poison and the absolute speed……………….the eternity of only one chance?

(Murobushi 2005; my translation)

It appears evident how his radical resistance devoured and exhausted even dance, the art form he caustically questioned until his last breath. Murobushi faced unremittingly death and the decaying body in his performances. In 1970 he declared in his diary notes: “The moment I decided to die I started to dance” (Murobushi 2015; my translation).

Death, the outside and his anti-dance are intimately concatenated (Centonze 2013). Also his programme notes addressing Sister Morphine, choreographed for Komatsu Tōru (Morishita Studio, Tokyo, June 2013), explain:

For Komatsu Tōru’s Unfathomable Hetero-Morphing

Sister Morphine dances the unremitting self-dismantling. No, she cannot dance. Instant and continuance. By doing so she cannot stop dancing.

This is because nothing but her death produces her life.

This is “the power that makes us unlimitedly blind.”

This is “our perpetual death, something we never can own as our own, it is constantly outside us, but it cannot be anything else than our death which always exists already there, where it has been craved as a trace.”

(In quotation marks quotes from Kobayashi Yasuo’s The right to impossible things.)

(Murobushi 2013; my translation)

A profound research and intellectual investigation backgrounds his actions and aesthetics, which often have been received as a sort of style to be imitated. Needless to say, that Murobushi’s stage presence is unique and unreproducible, because of the permanent experimental quality inherent in his corporeal works. It is certainly not sufficient to attend some of his workshops for becoming a butō dancer or for grasping the essence of his art.

He always reflected himself, his counter-discourse and his choreic exploration in several thinkers, and he was able to reduce the distance between philosophical thought and corporeal enactment. Without betraying the ideas which sustain his dance investigation, his nikutai responded concretely to speculations which intrigued him.

This great artist pushed the ephemeral body to dangerous limits without spectacularising his abilities. Conflicting forces conflate into his dance/anti-dance nourished by contradiction and paradoxes, which are materialised by his carnal body.

His outstanding commitment to dance as a political act, often misinterpreted, his dissident attitude towards the system brought him to savour situations as an isolated, solitary and independent artist (Centonze 2008b). His artistic coherence coincides with his political engagement. He intervened in social problems through his critical dance soaked with denouncements and insurgence. In this sense he realised Hijikata’s project of anti-dance as guerrilla, as an attack to the establishment.

Throughout his carrier Murobushi conserved and pursued pureness, not in style and form—although his dance reached a high level of refinement—, but in his corporeal counter-discourse which underpins his performative act and manifests a continuous challenge to his own body. Due to his idiosyncrasy towards mystifications, spiritualistic or religious purposes in art, his distorting lyricism gives birth to striking anti-fictional moments constantly in collision with the narrativeness of the theatrical act and the narrativity of the Japanese identity.

His dynamics and stillness reveal an endless friction between his blood and skin. It seemed as his body was entrapped in its Japanese identity, although, at the same time, Murobushi’s passion for discussion and provocation brought him to express himself to the utmost in his native language. For all these years this contrast spurred him on to move abroad and search for different places outside Japan, where he is known as Ko Murobushi.

Now, I have been living close to his place since 2007, connected by the Kanda River, whose cherry blossoms he loved so much. During these 8 years our companionship has gained more and more in confidence. Although I attended in Japan his festival “Soto” no senya ichiya—Outside (2013), and his works such as Mimi (2008), a ball (2009), The Back (2012), Krypt (2012), until his last performance in Tokyo, Sokkyō Dancing in the Street, at Roppongi Art Night (2015), I may recognise his long absence from his country and his relentless touring overseas. This makes me reflect and wish he would have been taken more into consideration by the Japanese theatre world.

Reference List

Centonze, Katja. 2006. Nuove configurazioni della danza contemporanea giapponese. In Atti del XXIX Convegno di Studi sul Giappone, 83-99. Venezia: Cartotecnica Veneziana Editrice.

——2008a. Finis terrae: butō e tarantismo salentino. Due culture coreutiche a confronto nell’era intermediale. In Atti del XXX Convegno di Studi sul Giappone, 121-137.Galatina (Lecce): Congedo Editore.

——2008b. Resistance to the Society of the Spectacle: the ‘nikutai’ in Murobushi Kō”. In Global COE Programme. Theatre and Film Studies 2007, vol. 1: 85-110. Tokyo: International Institute for Education and Research in Theatre and Film Arts, Waseda University.

——2009. Resistance to the Society of the Spectacle: the ‘nikutai’ in Murobushi Kō. In Danza e ricerca. Laboratorio di studi, scritture, visioni 1 (0) (October), 163-186. http://danzaericerca.cib.unibo.it/article/view/1624.

——2010. Bodies Shifting from Hijikata’s Nikutai to Contemporary Shintai: New Generation Facing Corporeality. In Avant-Gardes in Japan. Anniversary of Futurism and Butō: Performing Arts and Cultural Practices between Contemporariness and Tradition, ed. Katja Centonze, 111-141. Venezia: Cafoscarina.

——2011. Topoi of Performativity: Italian Bodies in Japanese Spaces/Japanese Bodies in Italian Spaces. In Japanese Theatre in a Transcultural Context. German and Italian Intertwinings, eds. Stanca Scholz-Cionca and Andreas Regelsberger, 211-230. München: Iudicium.

——2013. Hijikata Tatsumi and Murobushi Kō: Out of Dance, Out of Existence. In 外 Outside. Essay collection for Festival〈外〉の千夜一夜 Outside, eds. Murobushi Kō and Watanabe Kimiko, Akarenga, Yokohama (November 19th -24th).

——2014. “La danza contemporanea giapponese: Il corpo tra tecnologia e natura”. In Mutamenti dei linguaggi della scena teatrale e di danza del Giappone contemporaneo, a cura di Bonaventura Ruperti, 314-348. Venezia: Cafoscarina.

——2015. “Butō, la danza non danzata: culture coreutiche e corporalità che si intersecano tra Giappone e Germania”. In Butō. Prospettive europee e sguardi dal Giappone, eds. Matteo Casari and Elena Cervellati, 102-122. In Arti delle performance: orizzonti e culture 6, Università di Bologna, Dip. delle Arti. http://amsacta.unibo.it/4352/

Murobushi, Kō. 2005. quick silver. Unpublished notes of the artist. Tokyo.

——2013. Sister Morphine. Programme notes Sister Morphine (trans. Katja Centonze), Morishita Studio, Tokyo, 6 June 2013.

——2015. In Tsuitō bunshū “Soto” e! “Kōtsū” e!— ArigatōMurobushi Kō, ed. Nakahara Sōji. Kō&Edge.

室伏鴻と向き合うKo Murobushi

──日本の中の異邦人、身体の中の異邦人──

カティア・チェントンツェ

2015年6月、日本を代表するダンサー室伏鴻の突然の死は、日本のダンス界にとってとてつもないショックだった。室伏はダンスの新しい感性を世界中に広めた。生の肉体をふるわせて、独自の身体芸術を追究し、多くのアーティストや観客を挑発し続けているところだった。

舞踏/Butohを海外に広める中心的な位置を占めていたのが室伏であった。「背火&アリアドーネの會」に振り付けて、パリで1978年に上演された『最後の楽園 (Le Dernier Èden –Porte de l’au-delà)』 の時から、世界中のコンテンポラリーダンス界にも刺激を与え、新しいダンスの方法と流れを喚起し続けていたのも彼だ(Centonze 2006; 2010; 2014; 2015 参照)。

コンテンポラリーダンスと60年代の前衛であった舞踏とを結び付け、舞踏の実験的試みを刷新した役割も大きい。そうして彼は、若いダンサー達と活動を共にし、彼らの身体を鍛え続けていた(Centonze 2010; 2014)。

室伏は、土方巽が行ったダンス革命の最も重要な継承者の一人であったことは疑いがない。アンチダンスという師のラディカルな企みを育みつつ、それに対する自分自身での答を練り上げて独自の道を歩んだのだ。

私が室伏鴻に最初に会ったのはラヴェンナで行われたフェスティバル、Ottobre Giapponese(「日本の10月」第1回、2003年)の時だった。総監督のマルコ・デル・ベネが私に舞踏セクションのキュレーションを任せてくれたので、私は捨て身の覚悟で敬愛するダンサーの室伏鴻にお願いをした。驚いたことに、彼はすぐに了承し、照明のクリシャ・ピプリッツを連れてはるばる来てくれた。ビザンツの街ラヴェンナでは、室伏の力強いワークショップや私の講演が行われ、ラシ劇場で上演された彼のソロ『Edge 01』は感銘を与えた。あれほどのアーティストが、初めて会う私のような者に対してあまりに気さくでオープンなのに驚いたその時以来、友人としての関係がずっと続いた。時には果てしない議論を行い、時には言い争いになることも、この友情あらばこそだった。

ラヴェンナでのイヴェントからしばらくして、私は1年間のリサーチのために東京に赴いた。それは彼の作品にじかに立ち会える絶好の機会だった。男性ダンスカンパニー「Ko & Edge」を立ち上げばかりで、彼は公演の前も、終わってからも、いつも私を巻き込んで議論をしていた。Ko & Edgeの『美貌の青空(2003)』、『Heels (2004)』、女性のカンパニー「ダンス01」の『ジゼル(s) (2004)』、彼自身のソロ『すべてはユーレイ (2004)』などが上演された頃だった(これらの作品についてはCentonze 2008b; 2009 を参照)。

2005年、オルヴィエートのマンチネッリ劇場で行われたアリアドーネの會の『Zarathustra』(再演)に、彼は私を招いてくれた。売り切れになったその公演は、各地から訪れた観客で溢れかえっていた。

翌年の2006年、私はヴェネツィアで室伏と一緒に数日過ごした。もう1ヶ月以上も前から、室伏の銀色の身体のポスターでヴェネツィアは埋め尽くされていた。ヴェネツィア・ビエンナーレの国際舞踊祭のその年のテーマは「皮膚の下 (UnderSkin)」であり、そのために伊藤みろが撮った写真だった。室伏は、ソロ『quick silver』を2日間上演したが、1日目と2日目は、美学的な顕れにおけるテンションも色合いもまったく異なり、彼自身の別の面と異なるパフォーマティヴな行為を探ろうとしているように見えた。

その1ヶ月後にわれわれは再開した。室伏は、ヴェネツィア・ビエンナーレの第50回音楽祭で上演されたフリオ・エストラーダの『Murmullos del Pàramo』に出演した。

2007年、私の地元レッチェの田舎で開催されたフェスティバル Torcito Parco Danza I に、アンドレア・パーティとアンナマリア・デ・フィリッピと私とで室伏を招いた。私たちは、「ATNARAT」と題したサイト・スペシフィックなプロジェクトで、タランティズム(舞踏病の一現象)に関するポスト・モダンの神話を覆し、身体の歴史的重要性を再考しようと企画した。これは、文化的抵抗としてのタランティズムと舞踏に関する私の比較研究にもとづいた実験であった(Centonze 2008a)

さらには、この両方の現象に見られる死体のイメージを、このサレント地方──太古の石に囲まれ、弾圧と自己防衛の積み重なる歴史を持つこの地方──の厳しい自然の中で蘇らせたいとも考えていた。この異文化交流において、自分たちの歴史を書き換えようとしていたこの地のノマドのようなアーティストたちは、室伏のアイデンティティによってさらなる屈折を経験することとなった。その一方で、ドゥルーズ的ノマド性にこだわっていた室伏も、上演地のコンテクストの中に自らを映し出した。

室伏は2回上演した。最初の夜は、『quick silver』を特別版で再演。室伏の激しく炸裂するダンスは、観客に戦慄の波をひろげた。メタリックなアクリル・ペイントで覆われた裸体で繰り出す荒々しく暴力的な即興が、会場全体で展開され、空間そのものが有機的に活性化した。彼の肉体はまさに食細胞のように環境を食い尽くし、静寂が支配する会場を激しく攻撃した。その夜の室伏は、まったく妥協することなく、その場との対立的関係を表明したのだ。

タランティズムと舞踏とを組み合わせた私たちの企画は、これ以上望みようのないものとなった。室伏のパフォーマンスはただただ素晴らしいものだった。水銀がそうであるように毒でも薬でもある『quick silver』は、まるで毒蜘蛛のようにあたりをはいずりまわり、日本のアヴァンギャルド(室伏鴻)とサレント地方特有の現象(タランティズム)との間の闘争に火をつけたのである(詳しくはCentonze 2011)。

毒されていつつ、毒でもある、銀に塗られた彼の肉体は、様々なものに感染しながら揺動する彼のアイデンティティを反映しているようだった。そのようなアイデンティティの問題こそ、室伏がずっと追い続けていた問題だろう。

『quick silver』について、彼は次のように書いている:

「毒でもあり、薬でもあり、いまや無用にされたものとは、水銀、マーキュリー、メルクリウスですが、それは私たちのはぐれた身体でもある。(その答は、それが応答であり、伝令だから。)

私の身体技法のなかに、筋肉・骨・皮を硬直させ、バラバラに解体してしまう、あるいは全身を極限まで硬直させたところで一気に弛緩させる、内部と外部に隔てられた皮膚感覚をメビウスのように還流させ反転をさせてしまう、というようなものがあるが、毒薬の致死量や、絶対的な速度はいつものんでみないとわからない・・・・・一回のみの永遠?」 (室伏 2005)

室伏は最後の息を吐くまで、ダンスという形式を辛辣に問題視し続けていた。それゆえ、そのラディカルな反逆が、ダンスそれ自体をも貪り食い尽くしたのがはっきりと見えてくる。パフォーマンスにおいて、彼は絶え間なく、死と、崩れゆく体に対峙していた。1970年、彼は日記でこう宣言している――、「死のうとして 踊りをはじめた」(室伏鴻、2015)。

死、外、そして彼のアンチダンスは、密接に関連している (Centonze 2013)。小松亨に振り付けた作品『シスターモルフィン』のプログラム・ノートで、彼は次のように書いている。

「小松享の、果てしなき変形=モーフィングのために

シスター・モルフィン( Sister Morphine) はたえざる自己解体を踊る。否、彼女は踊ることができない。瞬間と持続。そうして彼女は踊ることを止めることができない。

なぜならほかならぬ彼女の死が彼女の生をもたらすからだ。

それは、〈われわれを限りなく失明させるような力である〉。それは、〈われわれの絶えざる死、けっしてわれわれのものとして所有することはできず、つねにわれわれの外にあるが、しかしつねにもうそこにある、そこに痕跡として刻まれているわれわれの死にほかならない〉。」

(〈……〉は、小林康夫「不可能なものへの権利」からの引用)(室伏 2013)

室伏の行為と美学を支えていたのは、このような深い探究と知的な考察だったのだが、しばしばそれは模倣しやすい様式として受け入れられてしまった。だが、いうまでもなく、室伏の舞台における存在感は、かけがいのない、再現不可能なものだ。それは、彼の肉体作品が、そもそもつねに実験であったからだ。だから、彼のワークショップに数回参加しただけで舞踏家になれるわけはないし、もちろん彼の芸術の本質を摑むことなどできるわけもない。

室伏は、自己を、彼の対抗言説を、そして舞踊的 (choreic) なほどの探究を、多くの思想家へと常に投影していった。さらに彼は、哲学的思索と肉体的上演とのへだたりを縮めることができた。彼のダンスによる探究を支えていた観念を裏切ることなく、彼の「肉体」は、彼を引きつけてやまなかった観念的思索に具体的に応答したのである。

この偉大なアーティストは、つかのまの身体で危険な限界まで突き進んだが、決して自分の技をスペクタクルにしようとしたわけではない。対立する力は、肉体に具現された矛盾とパラドックに育まれたダンス/アンチダンスの中に入り混じっている。

ダンスを政治的行為として行う彼の強い関与は、しばしば誤解された。体制に対する断固たるスタンスのため、彼は孤立や独立を余儀なくされたこともあった (Centonze 2008b)。彼の政治的関与は、アーティストとしての首尾一貫性と同居していたのである。告発と叛乱がしみ込んだクリティカルなダンスで、彼は社会問題に切り込んでいったのだ。その意味で室伏は、体制へのゲリラ攻撃としての土方巽のアンチダンスの企みを実現したといえるだろう。

室伏は最期まで、純粋性を保持し追求していた。彼のダンスのスタイル的、様式的純粋性という意味ではない――とはいっても彼のダンスは高度に洗練されていたが。ここで言っているのは、彼のパフォーマティヴな行為を裏打ちし自身の肉体への飽くなき挑戦を表明する、彼の身体的な対抗言説における純粋性のことだ。芸術における神秘化、スピリチュアル的目的、宗教的な目的に対して彼は非常に嫌悪を抱いていたので、そうした彼の歪んでいるリリシズムは、強烈な反虚構的瞬間を生みだした。これらの瞬間は、演劇的行為の「物語性」(narrativity) のみならず、日本人としてのアイデンティティが内包する「物語らしさ」(narrativeness) とも常に衝突し続けた。

彼の動の静は、血と皮膚の間の絶え間ない戦いを表している。彼の身体は日本人のアイデンティティに絡め取られているように見えるかもしれないが、同時にそれを問題視し挑発しようと、彼は彼の母国語で可能な限り熱く語り続けた。こうした軋轢が、ここ数年来、日本の外に場所を求めて彼を外国へと急き立てたのかもしれない。海外では、室伏鴻はKo Murobushiとして知られている。

私は彼の家の近くに、2007年から住んでいる。私の家と彼の家は神田川で結ばれていて、その川辺に咲く桜を彼はこよなく愛していた。この8年間で、私達の信頼関係はますます強くなってきたところだった。彼の作品は『ミミ』(2007)、『a ball』(2009)、『背面』(2012)、『Krypt』(2012) などを見てきた。彼が主催したフェスティバル『〈外〉の千夜一夜』(2013)もあった。そして、六本木・アートナイトでの即興『Dancing in the Street』(2015) が東京での最後のパフォーマンスになってしまった。彼は母国に長く不在だった、絶え間なく海外ツアーを続けていた、それも納得できる。日本の演劇・ダンス界がもっと室伏鴻に注目し、採りあげてもらいたかったと思う。

(翻訳:坂口勝彦)